Where Are the Mourning Politicians?

Due to work constraints, I took a break last week. I’m back, continuing my series of chasing the One Thing in the realm of politics.

Late Spring, 1992

Los Angeles burned.

I watched with passing interest from the living room of Middle America. Why the fires, the looting, the riots? Rodney King—a black man—had been kicked and beaten by a group of police officers, and the event had been caught on tape by a bystander. The officers were charged. Tried. Ultimately acquitted. And in the fury of this miscarriage of justice—one of many that spanned the decades—the people took to the streets. Liquor stores, grocery stores, fast food establishments—everything seemed to burn.

I was fifteen. White. A private-school gym rat whose hormones were ever turned to the next girl. South Central Los Angeles was a world away, and that though that world was a great conflagration, mine was not. And so, the message of the South Central rioters was lost on me.

Summer 2020

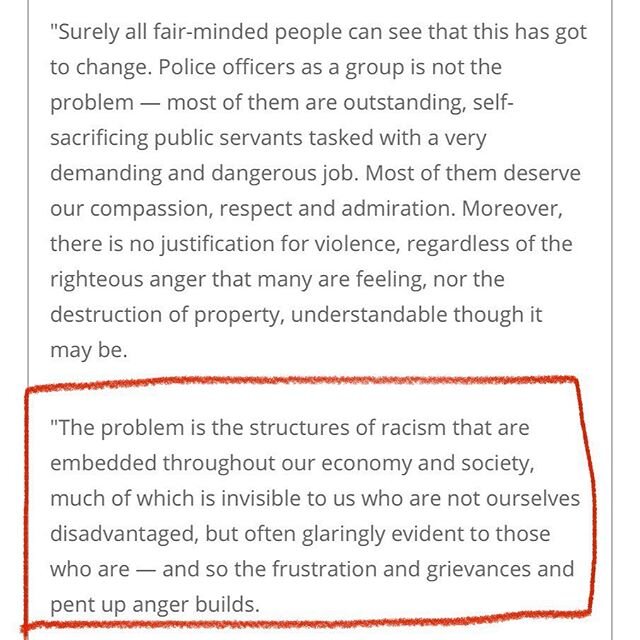

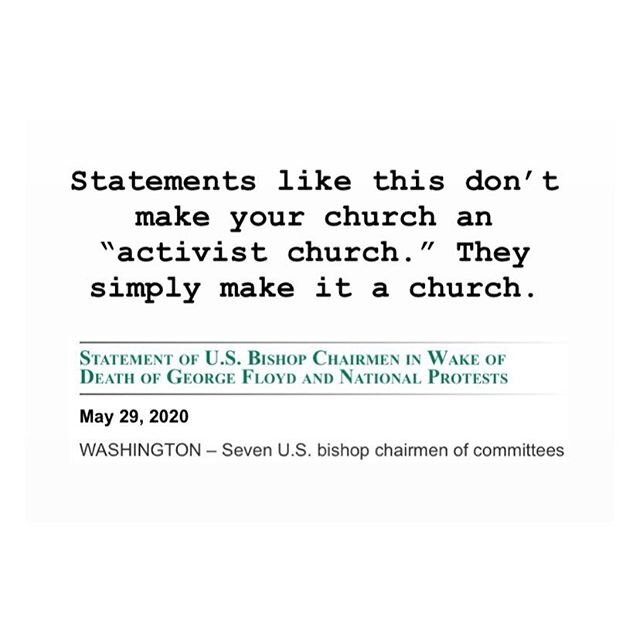

Almost 30 years later, and what has changed? Black men and women continue to suffer at the hands of authority. (Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, just to name the high-profile cases this year.) Demonstrators continue to march, continue to remind us that African American communities are underserved, over-policed, and systemically pillaged. Therapists are inundated with calls from patients who are suffering from racial trauma.

It’s been almost 30 years since I watched the burning of South Central Los Angeles, and little has changed, except maybe two things—the American powder keg has only grown more explosive, and I can see just how short the fuse is. But is there an appropriate political response?

“Blessed are those who mourn,” Jesus said, “for they will be comforted.” And as Jesus lived through sweat and dust, he found those mourning people—the woman caught in adultery, the Samaritan woman, the lepers. He sat with them, spoke with them, touched them. He comforted them in the present tense, not just with some ethereal promise of a heavenly reward. He was the embodiment of the ultimate good, what Soren Kierkegaard would call the One Thing.

If we were to chase after Kierkegaard’s One Thing, if we were to do our best to embody the true good, wouldn’t it mean comforting those who mourn? (And not just the African American community.) Wouldn’t it mean listening to the pain of the people and responding to it in empathy? Wouldn’t it mean using every means possible—politics included—to bring comforting solutions? Shouldn’t we vote for those who demonstrate the ability to hold space for people’s pain, to extend empathetic responses, to advance actual solutions?

These are not rhetorical questions.

We have come to the edge of another election season. As you consider voting in a way consistent with the One Thing, ask yourself:

Which candidates have demonstrated the ability to mourn the current state of affairs in America? and

Which candidates have shown the ability to bring comfort? and

If you don't see these kinds of politicians on the horizon, what does that say about us?

As always, my inbox is open if you’d like to share your thoughts.

![“It can be beyond our comprehension to even understand why someone would be hurting. [But] we can... understand that our brother and sister is hurting, and we can lean into their pain.” ~ @davidmbailey

I am white, and many of you here a](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56ba31db356fb05ecdc0b3bc/1591452672563-6H098FCYGTRU4I3378H9/image-asset.jpeg)