The Last Word on Politics (For a While)

The One Thing in Politics: A Final Word

This notion of chasing the ultimate good in politics (the One Thing) is not so simple. I’m no Pollyanna, and I have a pretty firm understanding of the complexities of the geopolitical world. A communicator by trade, I have some grasp of the war of words constantly waged by both the right-facing media and the left-facing media. I see the manipulations and know just how much it complicates the vote. I wish it weren’t so.

I’m closing this series out today because I’d like to move to other areas of examination. Before I do, I’d like to ask for mercy. Have mercy on me if we don’t see eye-to-eye on certain political issues. Have mercy on those politicians trying their best to keep a country churning. (I must admit I believe this to be a relatively small segment of today’s politicians.) I’d ask you to make peace with your neighbors, too. After all, what is peace-making but the attitude of mercy in action?

Of course, this does not mean you cannot have a political opinion, feel strongly about certain issues, or disagree with coworkers and family members vehemently. Instead, it means there’s no need to demonize others. As I said on Twitter this weekend,

Your weekend reminder: You can profoundly disagree with someone's rationale without demonizing them.

— Seth Haines (@sethhaines) July 25, 2020

Save demonization for actual demons.

We live in a world full of vitriol, hate, propaganda, and vitriol. As we lean into the upcoming election, it’ll only get worse. Let mercy and peace-making be your rubric as you chase the One Thing in politics this year. See if it doesn’t change your relationships. See if it doesn’t bring something like unity.

Yes, I’m moving on from this series, but if you’d like to drop me an email about this series, feel free to click this link.

Complexity Defies Political Absolutes

I’m continuing my series of chasing the One Thing in the realm of politics.

Linen Season, 2020

Here is the rub: When you follow after the One Thing—the ultimate Good—you’re bound to see all the roadblocks the world erects. For instance, assume you’d like a new pair of linen pants because it’s summer and linen is, after all, the greenest of green fabrics. In an attempt to advance the ultimate Good—stewarding the gift of creation—you find the perfect pair online at a rather large retailer. The fabric is made from organic cotton, chemical-free dyes, and is priced to fit your budget. And yet, who made the garment? Children in a sweatshop? Women in Southeast Asia who are paid less than a livable wage? And by purchasing those pants, what’s the economic impact on those communities?

This is a silly example, Seth.

Perhaps you’re right. Still, it’s an easy example, one that demonstrates the complexity of every decision we make. (And for the record, I could have used any number of consumables: electronics, free-trade coffee, American-made vehicles.) This begs the question: In this interconnected and complex age, is it possible to make a single righteous decision?

There’s no straining necessary to see the natural corollary. We stand on the edge of another national moment. Another election. Another set of impossible choices (left or right). Is any move righteous?

I could argue the sides, of course, make a case for my potential candidate of choice. This is not the point of today’s piece, though. The point put simply is this: Any vote you cast is a sort of ethical compromise. (If you do not see this, please email me and I’ll do my best to explain.)

We can look back again to the good Teacher, Jesus himself. In his great sermon, he extended a measure of grace to the people living in a milieu of complex choices. “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,” he said, “for they will be filled.”

Hunger and thirst—it’s a word that contemplates emptiness, lack, perhaps impossibility. He might have said, “Blessed are those who do righteousness.” Instead, he chose his words more carefully.

The quest for righteousness—the ultimate Good—should drive our action, regardless of religious slant. And so, when it comes time to vote in November, we should hunger and thirst (i.e., hanker and hurt) for a righteous result, one that does the most amount of Good for the most amount of people, particularly those on the downside of advantage—the poor, the immigrant, those in the African American community, the working class, the prisoner. And hungering for that result, we should do (vote) accordingly.

Complexity defies an absolute. That does not mean we cannot hunger for best.

We all need to wake up. So, what are you waiting for?

Creating the World You Want to Inherit (Yes, This is About Politics)

Fall, 1984; Fall, 1988; Fall, 1992; Fall, 1996; ad infinitum.

Every four years, the candidates come out swinging. They, like Olympic athletes, have put in the long hours. They’ve trained, honed their quips, their zings. Their arrows are sharp. Daggers, too. And they stand on the world stage and cut each other. World without mercy. Amen.

Elections are blood sport, and if you don’t believe me ask any of the losers—Mondale, Dukakis, Bush I, Dole, Gore, Kerry, McCain, Romney, Hillary. It’s survival of the political fittest and no attack is too low. After all, the power to cripple is the power to win. After all, the one who can be crippled is not fit for the Presidency.

As I’ve grown older, this blood sport seems to have grown bloodier. And in these most recent years, with the advent of social media, We The People play more of a role. We take to social media to lambast, lampoon, perhaps harpoon candidates. We use real news, fake news, rumor, innuendo, and ad hominem attacks to score points against their opponents. We shame the opposition, too, particularly those who are less down with the right causes.

Win, win, win. At all costs win. No one wants to date a loser.

This is our motto.

I have been guilty of participating in this bloodsport, American as I am. But as we approach the election of 2020—an election that sure to be bloodier than any before—I’m considering a different way. I’m considering how to pursue the One Thing—the ultimate Good—as I participate in the election.

“Blessed are the meek,” Jesus said, “for they will inherit the earth.” It was a comment made to a people under the boot of Roman thugs. These people—people on the losing edge of the sword—carried revolution in the DNA and passed it down to their children. Still, in that powder keg of a political climate, the great teacher flipped the narrative. The world, he said, belonged to those not always trying to dominate it. The world worth inheriting, he said, belonged to the meek.

The American experiment is ripping itself apart, in part through the political process. But arrogance and anger and bloodsport will not give us the earth we want. Meekness, humility, kindness, generosity—these are the values we pass down to our children, in part because these values represent the kind of world we want or our grandchildren. You know this to be true. Right?

The election is coming. The bloodsport is coming. The shaming. The vitriol. The attacks. The news and fake news. Can we resist? Can we model a better way, a way that creates the world we want to inherit?

Grab a copy. Grab a copy for a friend.

Where Are the Mourning Politicians?

Due to work constraints, I took a break last week. I’m back, continuing my series of chasing the One Thing in the realm of politics.

Late Spring, 1992

Los Angeles burned.

I watched with passing interest from the living room of Middle America. Why the fires, the looting, the riots? Rodney King—a black man—had been kicked and beaten by a group of police officers, and the event had been caught on tape by a bystander. The officers were charged. Tried. Ultimately acquitted. And in the fury of this miscarriage of justice—one of many that spanned the decades—the people took to the streets. Liquor stores, grocery stores, fast food establishments—everything seemed to burn.

I was fifteen. White. A private-school gym rat whose hormones were ever turned to the next girl. South Central Los Angeles was a world away, and that though that world was a great conflagration, mine was not. And so, the message of the South Central rioters was lost on me.

Summer 2020

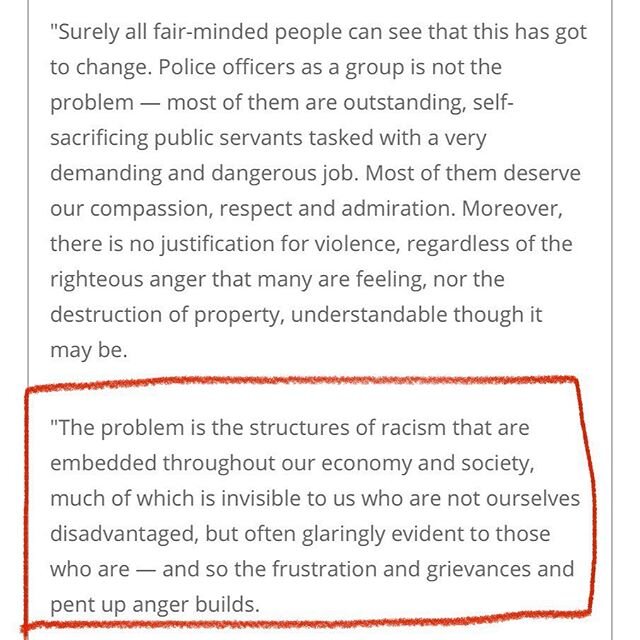

Almost 30 years later, and what has changed? Black men and women continue to suffer at the hands of authority. (Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, just to name the high-profile cases this year.) Demonstrators continue to march, continue to remind us that African American communities are underserved, over-policed, and systemically pillaged. Therapists are inundated with calls from patients who are suffering from racial trauma.

It’s been almost 30 years since I watched the burning of South Central Los Angeles, and little has changed, except maybe two things—the American powder keg has only grown more explosive, and I can see just how short the fuse is. But is there an appropriate political response?

“Blessed are those who mourn,” Jesus said, “for they will be comforted.” And as Jesus lived through sweat and dust, he found those mourning people—the woman caught in adultery, the Samaritan woman, the lepers. He sat with them, spoke with them, touched them. He comforted them in the present tense, not just with some ethereal promise of a heavenly reward. He was the embodiment of the ultimate good, what Soren Kierkegaard would call the One Thing.

If we were to chase after Kierkegaard’s One Thing, if we were to do our best to embody the true good, wouldn’t it mean comforting those who mourn? (And not just the African American community.) Wouldn’t it mean listening to the pain of the people and responding to it in empathy? Wouldn’t it mean using every means possible—politics included—to bring comforting solutions? Shouldn’t we vote for those who demonstrate the ability to hold space for people’s pain, to extend empathetic responses, to advance actual solutions?

These are not rhetorical questions.

We have come to the edge of another election season. As you consider voting in a way consistent with the One Thing, ask yourself:

Which candidates have demonstrated the ability to mourn the current state of affairs in America? and

Which candidates have shown the ability to bring comfort? and

If you don't see these kinds of politicians on the horizon, what does that say about us?

As always, my inbox is open if you’d like to share your thoughts.

If you have read it, today’s the day.

The Politically Poor in Spirit

Summer, 1992

In the church, a ceiling-sized flag was unfurled. It was God and Country Sunday, and the stars and stripes hung over every congregant. The choir led God and Country songs. The preacher preached a God and Sunday sermon. And to say I remember the content of those songs and sermons would be an imaginative fiction. Still, I was left with the distinct impression: Morality, Christianity, and the success of the American experiment were inextricably linked.

History of wars, slavery, poverty, inequity, classism be damned.

In my context, Christianity and the Republican Party were synonymous, and if it wasn’t directly spouted from the pulpit, it was implied. I was only fourteen. It’d be another four years before I could vote, but if I followed the suit of my spiritual teachers, I’d never vote for William Jefferson Clinton. The abortion advocate. The candidate who wanted God out of school. The alleged woman-monger. The supposed cocaine runner. The men on the other side, though, were paragons of morality.

Summer, 2020

As a child, I was given an easy rhetorical rubric that was to govern my voting choices: Republicans were Christians, and ergo, more moral leaders. But 28 summers later, that rhetorical rubric is a boat with holes. I’ve witnessed Republicans act with great virtue, and I’ve seen them fail morally. The same goes for members of the Democratic party. So, easy rubrics having failed, I’m left with a new question: How should I participate in political discourse (and voting) now that the easy rubrics of my youth are no longer helpful?

Jesus—a man some saw as a grassroots politician—came with a message for a very political people. Ready for revolution, for salvation from an oppressive regime, they were primed to fight. He came with a different message, though, and he shared that message in his great mountain sermon. If the people were to chase the One Thing, they’d need to embody his teachings. And yes, it’s my estimation that this applied to everything, politics included?

In his opening salvo on the mountain, Jesus preached, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” The Poor in Spirit—these are the people who lay hold of a heavenly political reality, he said. But who are the poor in spirit? Writing in the fourth century, St. Jerome put it this way: “[Jesus] added ‘in spirit’ so you would understand blessedness to be humility and not poverty.”

Those who embody true virtue, who chase after the One Thing, embody poverty of spirit. They are humble, repentant, know they don’t have all the answers. They put away easy rubrics and easy answers in order to search out the true Good. They do not rally behind the bombastic hubris of men.

If I were poor in spirit, if I were truly humble, how would this change the ways I approach politics? Would I shout down those who disagree on Twitter, would I cancel them? Would I make space for those with diverging views? And if I measured my political choices based on their poverty of Spirit (or the poverty spirit of their party), how would that influence my vote?

There are no easy answers to this question, perhaps. But as you consider poverty of spirit (i.e., humility) and its application to politics, what do you need to change to embody the principle? Better yet, what has to change in the American political discourse to advance a politics that is poor in spirit? As always, the inbox is open. Let me know your thoughts.

If you haven’t, go grab this book STAT,

and wake up from your addictions.

The Politics of Hate, Hunger, and Pride

Summer, 2020

Yesterday, I wrote of the 2016 election, how so much of my pre-vote wrangling and writing was driven by some need: to be prophetic; to be relevant; to be right. Looking back, perhaps I was prophetic, relevant, and right, but in the end, what difference did it make? Did I influence the course of the election? (Clearly not.) Did I advance the ultimate Good, the “One Thing.” (For more on the One Thing, do not miss yesterday’s post.)

Heading into another parade of horribles—What else is an American election but an endless march of madmen wearing grotesque masks?—I’m taking a different approach. But before I dive into the meat of the matter, let’s give definition to the problem.

To borrow from twentieth-century French philosopher Jaques Ellul, the problem is that: “Hate, hunger, and pride make better levers of propaganda than do love or impartiality.” And to be clear, these are not partisan levers. Politicians from the left, right, and middle all know this to be true.

Does this ring true of today’s political milieu? Do you see politicians using hate, hunger, and pride to divide and conquer the people? Are they listening well? Are they taking a hard look at the history of a country and asking whether our current policies are based on equity and impartiality (hallmarks of love)? Are they operating in another way, perhaps in furtherance of their own best interests? Has the motto of the politicians become, as Carl Sandburg put it,

“Love your neighbor as yourself but don’t take down your fence.”

(You cannot have it both ways, says uncle Carl.)

I realize I’m wading into boiling rivers here, that some of you might not want to discuss politics and its confluence with religion or faith or virtue or whatever. Still, the tutu-ed elephant is dancing in the living room, so let’s address it. And let’s do it a way that looks toward the ultimate Good, the One Thing.

Today, feel free to shoot me an email and share how you’re feeling about the current political climate. I promise to read your response with all the grace in the world. And though I might not respond to everyone, if I do, I promise not to pick a fight. After all, it’s hard to pursue the One Thing when your fists are flailing at your neighbor.

Next Up: How poverty of spirit should influence our politics…

Are you addicted to booze, boobs, or a political party? Wake up!

Join me on Instagram. Everybody’s doing it!

The One Thing That Governs My Politics

“But purity of heart is to will one thing.”

~Soren Kierkegaard

Summer, 2016

You may remember the heat. The sweltering news cycle. The churn and boil. I do. I was a man on a mission.

I’d evaluated the political landscape, noted the sparse options, and found some were sparser than others. A new kind of public figure dominated the news cycle, one my grandfather might have described as “wearing a silk suit without underwear.” The illusion of flash and bang. The cloying sugar of nationalism without the substance of meat. Signaling virtue without practicing it.

That summer, I sounded that sirens. I pulled from the fixed past to show the potential future. I wrote about it. I Tweeted about it. I took to Facebook to made a record. And if I could have willed one thing, it would have been that the great hoard of American middlemen would have come with a tarry rail, placed the public figure atop it, and carried him back to his penthouse. I did not will hard enough.

Four years have passed, and I do not feel vindicated. My fixation on the fixed past and potential future changed nothing. I suspect it changed nary a heart nor a mind. In fact, I suspect it built walls higher and longer than those promised to our southern border.

The election is upon us, and we’re again entering another season full of flash and bang (from both sides). Here comes the bullying. Here come the promises. Here come the single-issue appeals, the casting of moral imperatives, the in-or-out narratives. Waive the flags. Promote the party. Shoot the fireworks. This is Americana applied to politics. We like our process like we like our Whiskey, full of heartland pride and fire.

This year, I'm taking a different tact than I did in 2016. Why? Because I’ve woken in a world that’s so damned divided it’s hard to have empathy for those on either side, even with feet firmly planted in the middle. There are times I do not recognize the face of my brother, sister, or friend. There are days when the only question I find myself asking is, “Yeah, but what is their play?” I have bent to cynicism. I suppose that’s a confession.

So What’s My Play?

I was taking a break from the workweek, streaming some Sunday content by a Catholic Bishop. In it, he paraphrased Soren Kierkegaard, and I’ll paraphrase his paraphrase: The secret of Saints is to chase after the One Thing. Considering the line, I recognized how much of my 2016 wrangling had nothing to do with chasing the One Thing. In fact, it had more to do with chasing the wrong thing. The temporal thing. The ego-satisfying thing. I wanted to be on the right side of history. I wanted to make my record.

Don’t get me wrong, I still have political opinions, and they’ll come spewing out in terms too forceful from time to time. But this year, I hope to approach my political decisions from a different angle. Instead of aligning for or against a political opponent, I hope to examine the field from the position of the One Thing. How? I’m not exactly sure just yet. I’ll work it out here, starting with Jesus’ grand Sermon on the Mount. (And if you’re not a Christian, hang with me; the principles are generally applicable.) I’ll examine what it looks like to align with the One Thing, to chase the One Thing, to act in a nature consistent with the One Thing.

What is the One Thing? As Kierkegaard puts it, it is to chase after the Good. And what is the Good but God himself?

A Caveat

If you’re a member of my real-life community, you’ll likely see me run afoul of this One-Thing principle. Let me know. I’m a big enough boy to take the criticism. And please know, this does not mean I will not share my opinions on occasion. It simply means I’ll try to do it in a manner more consistent with knowing, serving, loving, and chasing after the One Thing. (Hint: That One Thing is not a political party or figure.)

![“It can be beyond our comprehension to even understand why someone would be hurting. [But] we can... understand that our brother and sister is hurting, and we can lean into their pain.” ~ @davidmbailey

I am white, and many of you here a](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56ba31db356fb05ecdc0b3bc/1591452672563-6H098FCYGTRU4I3378H9/image-asset.jpeg)