Complexity Defies Political Absolutes

I’m continuing my series of chasing the One Thing in the realm of politics.

Linen Season, 2020

Here is the rub: When you follow after the One Thing—the ultimate Good—you’re bound to see all the roadblocks the world erects. For instance, assume you’d like a new pair of linen pants because it’s summer and linen is, after all, the greenest of green fabrics. In an attempt to advance the ultimate Good—stewarding the gift of creation—you find the perfect pair online at a rather large retailer. The fabric is made from organic cotton, chemical-free dyes, and is priced to fit your budget. And yet, who made the garment? Children in a sweatshop? Women in Southeast Asia who are paid less than a livable wage? And by purchasing those pants, what’s the economic impact on those communities?

This is a silly example, Seth.

Perhaps you’re right. Still, it’s an easy example, one that demonstrates the complexity of every decision we make. (And for the record, I could have used any number of consumables: electronics, free-trade coffee, American-made vehicles.) This begs the question: In this interconnected and complex age, is it possible to make a single righteous decision?

There’s no straining necessary to see the natural corollary. We stand on the edge of another national moment. Another election. Another set of impossible choices (left or right). Is any move righteous?

I could argue the sides, of course, make a case for my potential candidate of choice. This is not the point of today’s piece, though. The point put simply is this: Any vote you cast is a sort of ethical compromise. (If you do not see this, please email me and I’ll do my best to explain.)

We can look back again to the good Teacher, Jesus himself. In his great sermon, he extended a measure of grace to the people living in a milieu of complex choices. “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,” he said, “for they will be filled.”

Hunger and thirst—it’s a word that contemplates emptiness, lack, perhaps impossibility. He might have said, “Blessed are those who do righteousness.” Instead, he chose his words more carefully.

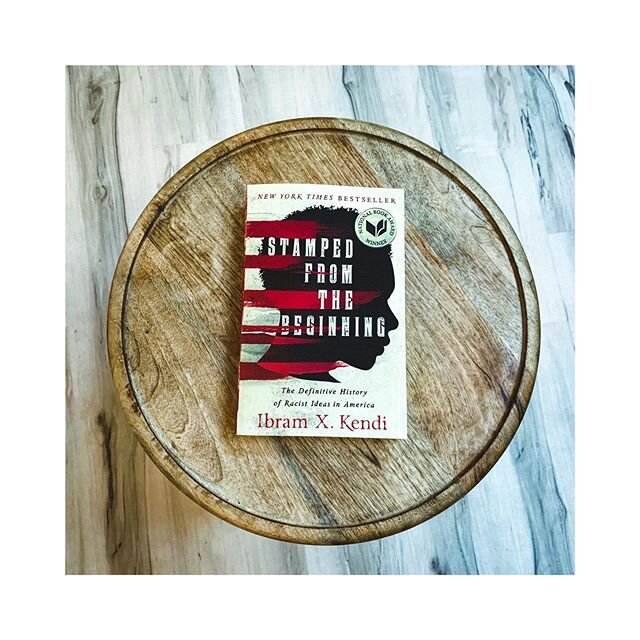

The quest for righteousness—the ultimate Good—should drive our action, regardless of religious slant. And so, when it comes time to vote in November, we should hunger and thirst (i.e., hanker and hurt) for a righteous result, one that does the most amount of Good for the most amount of people, particularly those on the downside of advantage—the poor, the immigrant, those in the African American community, the working class, the prisoner. And hungering for that result, we should do (vote) accordingly.

Complexity defies an absolute. That does not mean we cannot hunger for best.

![“It can be beyond our comprehension to even understand why someone would be hurting. [But] we can... understand that our brother and sister is hurting, and we can lean into their pain.” ~ @davidmbailey

I am white, and many of you here a](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56ba31db356fb05ecdc0b3bc/1591452672563-6H098FCYGTRU4I3378H9/image-asset.jpeg)